UFU holds discussions with DAERA on GB cattle imports

Like many farmers in Northern Ireland, the member had recently bought a pedigree bull in Carlisle. However, he was frustrated when the bull had to be sent back to the selling herd for 30 days before being allowed to move to Northern Ireland. This process added over £600 of costs to the farmer due to housing, feeding, veterinary and haulage expenses.

Furthermore, when the bull eventually did arrive on-farm in Northern Ireland, the farmer reported that it was a shell of the animal that he had bought at the market as the seller had reduced the amount of meal he had been feeding the animal during that period.

Advertisement

Advertisement

In light of this, the UFU asked DAERA to highlight and explain the rules governing the current policy and to see if there is any avenue that could be explored to lessen this financial burden on farmers who wish to import stock from Great Britain and the EU.

The principal legislative framework that governs the trade of breeding livestock between EU member states is Council Directive 64/432/EEC. This Directive enables animals to move between EU member states subject to animal health rules and Veterinary certification. Articles 3 and 6 of the Directive require (amongst other things) that the animal has to come from an area with no health restrictions, pass an identity check and undergo a clinical inspection by a Vet within 24 hours of departure.

Additionally, an animal has to remain on a single holding for 30 days prior to loading (including moving through an approved assembly centre), and has to come from an officially TB & BR free herd.

Trade between GB and NI, on the other hand, is based on licensing requirements drawn up by DEFRA and DAERA respectively. Whilst these requirements are based on elements of 64/432 they are less onerous in certain aspects. However pre-export TB testing in GB is still required and given the current TB prevalence in much of England and Wales and the fact that some regions are only testing every four years this is to be welcomed from a NI viewpoint. This approach helps to ensure that farmers do not inadvertently import TB infected animals into Northern Ireland and particularly into high value pedigree herds which would result in large compensation costs and loss of valuable blood lines.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Obviously, the choice to impose this regionalisation approach is a decision that is made on balance (i.e. there is a cost imposed on the industry due to these rules. However, there is also a benefit due to maintaining our national health status and ability to export our produce).

Whilst quantifying and comparing such a cost/benefit is a complicated task, DAERA provided the committee with information on the number of cattle imported for breeding from GB over the last five years (1,784 cattle per year on average) which could be multiplied by the £600 cost suggested by the farmer. This sum suggests that our regional policy adds costs of roughly £1,044,000 per year or £2,860 per day on to the industry for those that wish to import cattle for breeding into Northern Ireland.

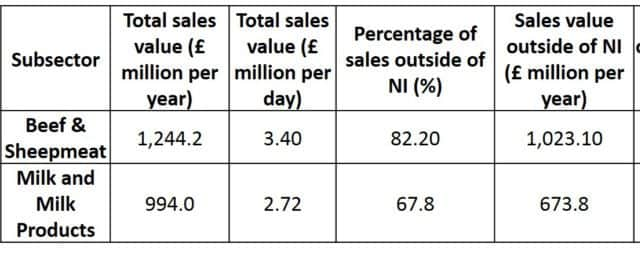

However, this pales in comparison to the value of our export sales and gross value added to the economy which stand respectively at £2.8 million and £370,000 per day for beef and sheepmeat combined and £1.84 million and £220,000 per day for milk and milk products (See Table 1).

As such, our regional control approach protects Northern Ireland farmers and food processors and enables us to maintain our export markets when other parts of the UK are experiencing a disease outbreak (e.g. Foot and Mouth or Bluetongue). Additionally, this regionalised disease approach is what is enabling Northern Ireland to apply for BSE negligible risk status ahead of our GB counterparts.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Furthermore, with Northern Ireland’s dependance on export markets (i.e. we export 82% of our beef and sheepmeat and 68% of our dairy products, whereas the UK as a whole is only around 60% self sufficient in food), maintaining a high animal health status is arguably more important for us than it is for the rest of the UK. It is for this reason that the UFU has identified establishing Northern Ireland as an international centre of excellence for plant and animal health and breeding as one of its priorities for the new Northern Ireland agricultural policy.

Whilst this approach does little to reduce the cost and inconvenience for farmers looking to import cattle, it is a decision that has been taken on balance as it serves the greater good of protecting our export focused industry. However, the UFU would point out to farmers that some pedigree sheep societies have established export sales in GB, where all pre-movement requirements have been completed before moving the animals to the assembly sale.

Since all animals in the sale have a similar and known health status, they are able to move directly from the assembly sale to the farm in NI. In theory, there is no legislative reason why such an approach could not be taken by cattle societies at which point this becomes a commercial matter.

The only reason why a GB farmer would want to go to the added cost and inconvenience of getting his animals pre-export cleared is if they thought they would receive more money for them and the only reason a Society would hold an approved export sale is if they thought it would generate a greater turnout and profit.

Advertisement

Advertisement

In theory, if they were to hold one export sale per year where all animals were export cleared, this may encourage more importers from Northern Ireland and Republic of Ireland to attend which would increase demand, and given that each one of these farmers would have roughly £600 extra in their pockets because they would no longer have the additional expenses associated with importing, then they could afford to increase what they paid for these animals which would give the GB farmer a motive to go to the effort of having the animals pre-movement cleared.

All of these are commercial decisions that have to work to the benefit of all parties involved to be sustainable. However, it is a model that has been shown to work for sheep and there is little reason to think it could not also work for cattle.

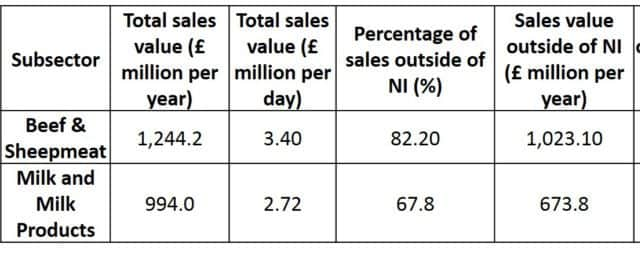

In order to target discussions on this topic, the UFU has obtained information on cattle imports by breed (see Table 2) and will initially approach the larger societies in order to establish a framework and ascertain whether such an approach would be viable before approaching smaller societies.