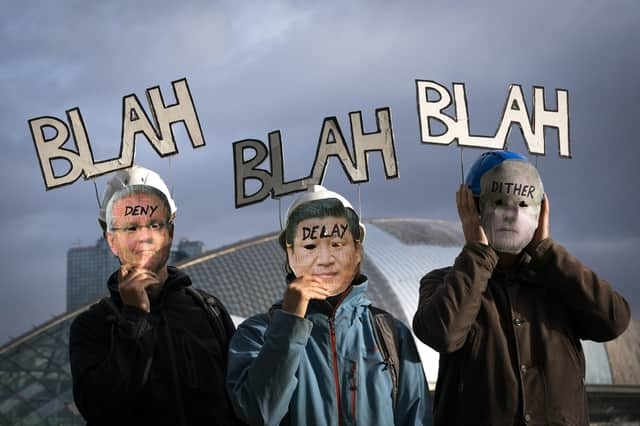

COP 26 fails to live up to its billing

It however proved as much of an anti-climax as most of the previous 25 COPs. The 2022 session will now be another last chance, but in reality the political appetite for change is lacking.

The focus on big ideas and big plans simply does not deliver.

Advertisement

Advertisement

China and Russia will go on generating power from the dirtiest of dirty coal plants; the US, as a major producer and user of coal, will be secretly relieved this let it off the hook.

The pledges and promises of money in the future are largely empty gestures. Despite the spin the government put into making the event appear a success nothing that emerged will have much impact and that will remain the case until the big polluters are forced to act.

It was ironic that beyond the criticism it faced in the debate around the methane pledge food and agriculture made no impact at COP 26. This is despite food being key to global survival, while agriculture is a part of the solution, as well as one of the many contributors to climate change. As with coal, political expedience won the day. In reality there needs to be a greater focus on how food is produced. Countries need more freedom, under international trading rules, to demand that those supplying them meet the standards their own farmers have to meet.

This is an area where both the UK and EU are weak. It is a fatal flaw to pursue green policies for agriculture in isolation. If they do not demand similar standards for imports, products will simply come from overseas to meet demand, be that for meat or dairy products. This is the concept of carbon leakage. In other words the problem becomes out of sight, out of mind.

Advertisement

Advertisement

The sacrifices by local farmers to meet net zero targets cause pain for them but have no impact in a global context. Indeed this approach could make things even worse, because environmental standards will be lower in the countries where the food is now being produced. COP 26 was all about grandiose global initiatives to make politicians look effective, but real success is more likely to come from cumulative impacts that result from local measures that are practical and deliverable.

With climate change out of the headlines inflation has now replaced it as the issue of the moment. The UK rate of inflation, which has now topped four per cent, is at its highest level for almost ten years. Rising prices have taken over from Brexit problems as the main topic of social conversation and farmers are at the sharp end.

The United Nations Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO) October global price index painted a picture of rising commodity prices, led by cereals. Prices for wheat alone rose by five per cent from September to reach their highest level since 2012. Across other major commodities prices also rose, with even meat far ahead of where it was in the same month last year. This is the sort of news farmers like. Rising commodity prices impact what they receive more than rising shop prices, which tend to be absorbed by others along the food chain.

A dose of very cold water from the European Commission however hit that optimism. This came from the Irishman, Michael Scammel, who told members of the European parliament’s agriculture committee two factors alone were wiping out the gains from higher commodity prices. There are no prizes for guessing what these are – fertiliser and agrochemical prices. Even for the arable sector, enjoying good prices because of high production in Europe while it fell elsewhere, the rise in fertiliser prices alone wiped out the gains.

Advertisement

Advertisement

In a nutshell we have an example of how, even with prices at a twelve-year high for wheat, they are not enough to head off the rising costs. These are linked to energy prices and this is driving a tsunami of other rising costs for farmers including diesel, labour and building materials. This was well summed up in the European parliament, with one Irish MEP saying that for farmers the issue is not the end price, but profitability. That is true, but while others are passing cost rises on to their customers farmers, as the food chain’s weakest players, find it impossible to dodge the inflation bullet.