We need less politics and more economic reality

Back stop; back stop to the back stop; customs union; WTO tariffs. The list seems endless, but while we may know the words in the script we are no wiser about the future. The process remains akin to trying to nail the proverbial blancmange onto a wall.

There is an expectation that like CAP reforms there will be a last minute deal, with nothing agreed until everything is finally agreed.

Advertisement

Advertisement

That looks a big challenge, and we could yet see the ball kicked deep into touch again to delay when Brussels and London finally have to admit a deal is impossible.

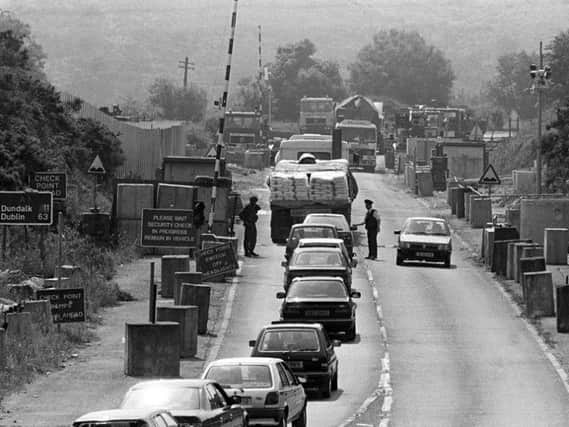

It is bizarre that the border and back stop have become the stumbling block. Theresa May, or her officials, must have realised what they were signing up to last December when they rushed to Brussels in the early

hours to deliver a ‘breakthrough’. Instead it has become the deal blocking a deal, with politics and economic common sense seemingly on tracks going in opposite directions. The only conclusions can be that British officials did not understand what they were agreeing to, because this and the resulting bad relations at Westminster are a self-inflicted problem. This is an inescapable conclusion, whether you are a Leave or Remain supporter.

Farmers and the food industry want some measure of certainty and that is not emerging. We need less politics and more economic reality about the options this debate is narrowing down to, as the real deadline for a decision one way or the other approaches. When it comes to trade, what we need to consider is what we have now versus what the future would bring in a deal or no deal scenario. There are various permutations, based around some form of customs union, but the no deal outcome is easier and more scary to forecast.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Farmers and the food industry here now have free access to one of the best markets in the world, in the EU 27. That would continue in a customs union, but Brexit supporters are against anything that would limit the scope of the UK to sign global trade deals. The big prize they want is the United States, but the track record of the Trump administration on trade deals is not impressive. Most of the countries of the Commonwealth are too poor to be trade prospects. The prosperous, like Australia and New Zealand, are already in discussions with the EU on a trade deal. Canada too has a deal with the EU. For these countries trade with the UK and its 60 million population is not an economic priority.

A customs union of some type with the EU remains the best option. This would allow products, such as lamb, continuing access to EU-27 market. Critics of this approach will say it also allows countries in the EU-27 to supply food into the UK. This is true, but the UK is only two-thirds self sufficient, and UK suppliers could not step up production to fill that gap. Food coming into the UK from the EU-27 is coming from high EU standards, high cost producers. The industry here can live with that situation. It is also a trade relationship that brings export possibilities for the UK.

For the no deal option to deliver the UK would need to secure speedy deals. The attraction for many countries is that, unlike the EU, the UK wants trade to be on the basis of no tariffs. The government would be easily persuaded to include food. It would then let the market decide whether people want cheap imports or to pay a premium for better quality, locally produced food. That is an outcome that could close access to the EU-27. The question then is whether these new trading partners would make up the gap by buying from the UK. There would be possibilities for some specialist products and drinks, but not for mainstream agriculture. The government’s target list for trade deals includes the the United States, Brazil, Australia and New Zealand. They are all huge global food exporters with low cost farming industries.

Beyond those come China, India and others with a growing middle class population – but there for food the UK would be head-to-head with the US and EU. The time might now be right to introduce some new terms into the Brexit vocabulary. Reality, economic logic and common sense would be good suggestions.