January sees ‘Redwater’ discovery in County Down

and live on Freeview channel 276

A three-year-old beef cow was presented to Stormont VSD at the beginning of January, following sudden death while grazing near Strangford Lough in Co Down.

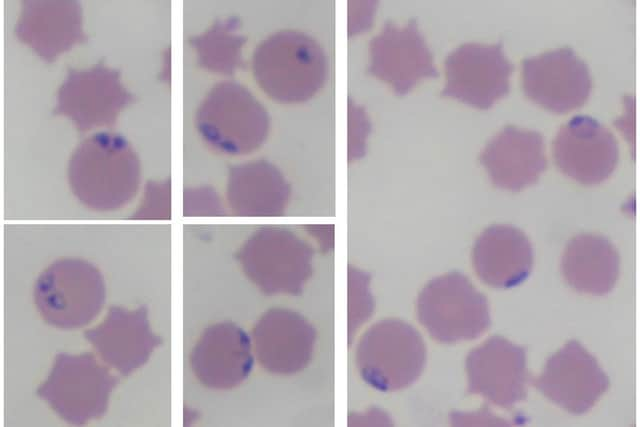

The cow had a tick burden and was diagnosed with babesiosis, initially on positive blood smear, and then by positive PCR for Babesia divergens. This was the first case of babesiosis identified in Stormont VSD for five years and was particularly significant given the unusual seasonal presentation of the disease.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Babesiosis is caused by an intracellular parasite of red blood cells (RBCs). There are numerous species of Babesia affecting different animals in different regions of the world, but in bovines in the UK it is mainly Babesia divergens.

The parasite relies on a tick vector; in Northern Ireland this is the Ixodes ricinus tick.

The female adult tick, nymph or larval stages become infected by ingesting parasitised RBCs and they can then pass this infection on in their eggs or to their next life-cycle stage. When they subsequently feed on other bovines the parasite can then be passed from the tick’s salivary glands into the bovine’s blood stream. Clinical signs begin around two weeks after initial infection.

Ticks have an environmental requirement for high humidity, which limits their activity to woodland, rough hill grazing, overgrown pasture and waterlogged low-lying areas.

Advertisement

Advertisement

As the infection relies on ticks, there is traditionally a peak in the number of cases, associated with ticks becoming active, in April to June and August to October.

From recent research in Ireland and the UK, the levels of babesiosis have decreased, however there have been reports of Babesia cases being detected in the winter. This finding is attributable to the effects of global warming, with 2023 being the warmest year on record for NI, with few episodes of freezing temperatures having occurred this winter.

Bovines less than nine months of age have an apparent immunity to the disease and if they are infected during this period, their immunity will persist provided they are repeatedly exposed to infection as adults. This is why cattle in areas endemically infected, and with a high tick burden, have few clinical cases in resident animals, with most cases occurring in brought-in animals. However there have been reports of babesiosis in calves under this age.

Babesiosis is a significant disease due to its morbidity and in some cases mortality for naïve animals, however even in endemic areas it can still affect fertility and productivity. The characteristic finding in cases with this disease, and why it is colloquially termed ‘Redwater’, is the red to ‘port wine’ coloured urine.

Advertisement

Advertisement

This is caused by haemoglobinuria, following the release of haemoglobin when infected RBCs rupture. Other clinical signs in the acute phase include fever, increased respiratory rate and pipe-stem diarrhea, while chronic cases progress to constipation, anaemia, low body temperature and jaundice. However, recent observations by farmers and vets note that the most common clinical sign detected on-farm is constipation.

Diagnosis of babesiosis on-farm is often based on clinical signs and history of recent movement into a known infected area, however blood smear analysis and PCR testing can be undertaken for a definitive diagnosis. Treatment may not be required in mild cases if the level of parasitism is low, and animals that recover are infected for a variable time with no clinical signs.

However, for the more severely affected animals, treatment involves chemotherapy with Imidocarb and an ectoparasitic, and perhaps blood transfusions and other supportive care. Treatment is best made on a farm- and animal-specific basis, in consultation with your vet. To prevent cases, it is important to identify areas most at risk and avoid grazing susceptible naïve cattle there.

Tick control is also important including, if appropriate, field drainage, clearing overgrowth and the use of long acting ectoparasitic treatment effective against ticks. It may be advisable to discuss with your vet about prophylactically treating suspected naïve animals moving into an infected area.

Advertisement

Advertisement

This is a reminder to vets and farmers to be aware of the changing annual and geographic activity of ticks, and to keep ‘Redwater’ on your differentials list in any tick-associated areas in Northern Ireland at any time of the year. Acknowledgement and thanks to colleagues in Department of Agriculture, Food and Marine for running the PCR analysis to confirm babesiosis.