Government looks at abandoning bid to halt rampant tree disease

Instead, the Department of Agriculture, the Environment and Rural Affairs is considering simply recommending that Northern Ireland try to live with the disease as best as possible.

The disease – called ash dieback – first appeared on the island of Ireland in 2012, after ravaging parts of continental Europe for years beforehand.

Advertisement

Advertisement

It afflicts all types of ash trees, which the Woodland Trust estimates make up about three-fifths of the trees in Northern Irish hedgerows.

It causes leaf loss and lesions on the bark, harms trees’ ability to transport water and nourishment, and ultimately kills them.

In some countries, ash has been virtually eliminated in just a couple of decades thanks to the disease, which has no known cure.

Ash dieback is fungus-based, and previously sites of infestation have seen trees and saplings ripped up and burned in an effort to control it.

Advertisement

Advertisement

However, DAERA has now told the News Letter: “Scientific opinion, and the evidence of the pattern of spread in continental Europe and Great Britain, suggests that continuing the approach of removing infected ash would not impede the further natural spread of the disease.

“The department invited the public to comment on a proposal, which it is currently considering, to change the focus of a compulsory eradication approach in favour of supporting owners to manage the impact of the disease in woodlands and to create woodland conditions under which any disease tolerant characteristics may emerge.”

It added: “It is not possible to state how many ash trees will be lost or how quickly.

“The disease has caused widespread damage to ash trees in continental Europe, where experience indicates that it can kill young ash trees quickly, while older trees can resist it for some time or until other endemic tree pests or pathogens attack the ash trees in their weakened state.”

CAN RESISTANT TREES BE FOUND?:

Advertisement

Advertisement

Patrick Cregg, head of the Woodland Trust in Northern Ireland, lamented the present position.

He said much of Ulster’s greenery “comes from its hedgerows because of the nature of our field patters”, and that “60% of trees in the hedgerows are ash trees”.

“Realistically there is a danger that they could disappear, which would have an effect on the landscape,” he said.

One of the first casualties of the diesease was his charity’s own Diamond Jubilee Wood in Whitehead, planted to honour the Queen in 2012, but largely ripped up mere months later after ash dieback was found in it.

Advertisement

Advertisement

However, he sounded a supportive note when it came to the idea of ending mandatory destruction of infected sites.

“When we spotted it [the disease] in the beginning, we thought you could control it by just eradicating it, destroying infected plants – which were all young stock at the time.

“As it has spread to the countryside, there’s no way you’re going to destroy every tree that becomes infected.

“We agree with the department – you shouldn’t slash and burn everything. By leaving ash trees, you may leave some that have built up a resistance.

Advertisement

Advertisement

“It is interesting – there’ve been cases where some ash trees had been affected and others in the area have not. But it is going to require some study in the coming years.

“Being realistic, ash will continue to suffer – it will be still under threat and will disappear in large numbers from the landscape. As a tree lover, it saddens me; a tree lover that’s old enough to remember the impact that Dutch Elm Disease had.”

He was referring to the disease which essentially wiped out all mature elm trees in Great Britain from roughly the 1960s onwards , amounting to about 30 million trees according to government estimates.

That disease continues to afflict their offspring today.

HOW FAR HAS IT SPREAD?

It was late 2012 when ash dieback was found in Co Leitrim, followed soon after by its discovery across the border in Northern Ireland.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Remarkably, the authorities north and south in Ireland only stopped the import of ash saplings from continental Europe once the disease had already been found on the island.

Initially infections were confirmed only in young, freshly planted ash trees.

But in 2015 the disease was found to have spread to established native trees in the wild in NI.

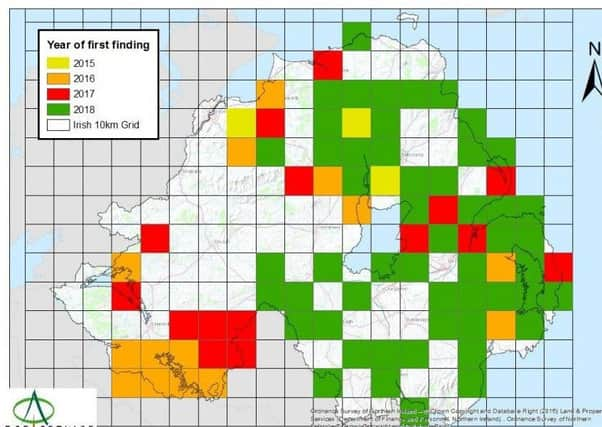

DAERA has now decided to measure the extent of the spread in the wild by dividing Northern Ireland up into a grid of 10km-by-10km squares.

Advertisement

Advertisement

If a square is coloured, it means an ash infestation in the wild has been found somewhere within that square since 2015.

Each square could contain multiple infected sites like parks or forests.

There were 84 such squares as of August 31 this year – with most of them having been found during 2018 so far.

In 2012, New Scientist magazine ran an article about ash’s future.

Advertisement

Advertisement

It said: “Although there are no official figures, ash trees have effectively been wiped out in Poland, where the disease first made its appearance in 1992. In Lithuania, 99% of the ashes are gone; in Denmark, 90%. Elsewhere, the impact has been mixed, with some but not all ashes succumbing.”

As to whether it can be stopped, the author said: “Apparently not. Most countries where it has taken hold simply gave up.”

See Morning View: The loss of all ash trees will be a sad outcome for rural NI